Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

Blog post 5

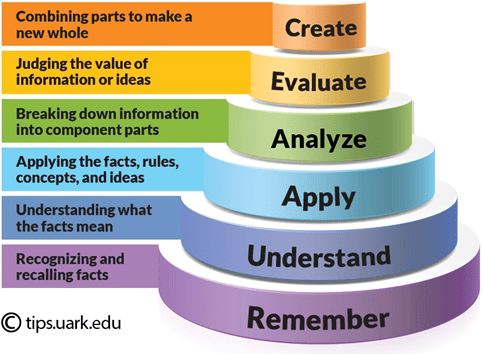

I think that in chapter 3 Larson brings up some salient points about assessment that are good for soon-to-be teachers to keep in mind. While everyone is in agreement (or at least most educators) that we do too much standardized testing and focus too much on grades and points, it is important not to push so far as to eliminate them altogether. It is impossible for administrators, district employees, parents, and community members to actively keep tabs on the progress of all students so we need a system that can provide aggregate data on all students within a class or school or district. Larson provides several ways to assess student learning that fulfills this requirement while also being dynamic enough to be helpful outside of the world of letter grades. I think the two powerful frameworks of cognitive and affective domain were especially helpful to me. While familiar with Bloom’s taxonomy I think it was both an important refresher and good to have it within the context of assessment. The section on affective domain was new information to me and I thought was also very important to understanding our students as complex emotional beings with biases, experiences, and conceptions. Larson also addresses how to design rubrics in a way that can accommodate the nuance of student understanding while still winding up with a tidy number scale. It is also worth pointing out to future or inexperienced teachers just how much agency the teacher has over deciding what constitutes a 3 out of 4 for example. There is still lots of “wiggle room” within the system for us to make decisions. Overall the chapter did a great job of reminding us that while it can be tempting to think we’re Robin Williams in Dead Poets Society we still need to provide hard evidence that the kids “get it” and unfortunately the best way to do that (that we know of so far) is formative, summative, and diagnostic assessment.

Blog Post 4

While I found the Schmidt chapter on primary sources very informative (and full of great examples), I think it is important to remember that when teaching history, the selection of primary sources is just as important as remembering to include them. History as a discipline requires us to consolidate events and eras down into smaller easier to digest chunks. If the class were studying the great depression it would not be practical to try to read every newspaper article, from every city, for every day of the era. Every single one of those stories would add some kind of color to inform our understanding of what life was like then, but at some point, you have to decide what stories are more important than others. Similarly, if the class were studying white American’s westward expansion and homesteading efforts it would be very informative but also very impractical to look at the farmers almanac for every day of the late 1800s. Even a PhD student with a specific focus on that era probably doesn’t have that much time. Schmidt has some great exercises and makes some great points, but I think she forgot to talk about how important and delicate the selection process is. The conclusion especially seemed to be a sales pitch that could be summarized as “social studies teachers should totally use primary sources” to which I think an overwhelming majority of social studies teachers would put up no counter argument. Maybe I’m not giving Schmidt enough credit, and maybe she addresses this in another excerpt somewhere, but it just seemed like something that needed to be addressed. I did however like the examples she gave and personally remember those types of exercises much better than dry textbook reading (if I ever really did my textbook reading like I was supposed to in high school) I think primary sources can be a very powerful tool for students of history, which is all the more reason that we should closely examine why we choose the ones we do. To be fair to Schmidt, I don’t have any golden rule or clear standard as to how to decide if the accounts of Roman peasant field workers are more or less important than the record from the treasury detailing the budgets for military equipment. This is the subjective nature that is inherent to doing history.

I liked Bain’s discussion about the seen and unseen aspects of history and how little unseen aspects are taught in public schools. For high schoolers, unseen aspects are difficult to work with because of the epistemic understanding required to move past the “fact-based suppositions of history”. I think we give our students and teachers too little credit, however, when we think that kind of work only belongs in graduate degrees in universities. History, like science, (without getting too caught up in comparisons between the two, they are very different in many other respects after all) is a process, as well as the body knowledge that is produced by that process. If we fail to teach our public school students that first half then we fail to teach them a key skill for fostering informed civic engagement. Bain lays out some pretty clear methods for fostering that kind of thinking when describing how he typically begins a semester. Journaling about the first day of school seems like a particularly powerful exercise because of the psychological power of experience. People have claimed some pretty ridiculous beliefs in the name of an experience they have had (or thought that they had). Having them journal about it and describe their experience so that they next day they can read it out loud to the class would be a fantastic way for them to see how easily different people can have such different accounts of the same event. I think this one exercise alone could go a long way in developing an epistemic understanding of the process of history, but Bain goes on to use a chart and more concrete classifications to make his points even clearer. I think that exercises like this are a clear example that historiography can be effectively understood by high school students. Why it is not implemented in every history classroom I am not sure.

(I know I used this video in my last post, but I think it was a fantastic one and maybe even a little more relevant to this reading. I also think that it took more time and effort to find the video and watch it than it would to grab an image from google so maybe you’ll count it for two images? If not that’s fine)

Lee brings up important points about the “doing of history” especially in regard to evidence and accounts, and how historians collect and analyze these. In many ways, historical integrity mirrors journalistic integrity. The practice of history requires finding reliable primary sources and comparing them to others in an attempt to find out “the truth”. Obviously, details are going to be exaggerated, wrong, or omitted and historians are left speculating as to what actually happened. Historians also need to be culturally literate. Depending on the particular culture and time period being studied, the source material may use different kinds of figurative language, forms of expression, or frames of reference. This is especially difficult because for many cultures and in many historical periods the idea of objective truth is not a very important one at all. A classic example is when the early historian Herodotus claimed that there were several million Persian troops at the battle of Thermopylae. Herodotus may have claimed to care more about historical accuracy than his contemporaries, but he was probably still more concerned about communicating how the battle must have felt to the Greek forces than he was about making sure his figure was realistic. This makes things difficult for modern historians. Another famous example is the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, a work of literature written about the Three Kingdoms period of China. This work is not intended to be factually accurate, but can we fault its author? It was written before digital records could be kept, before scientific dating processes had been developed, and even before widespread literacy. If you lived in a world where I could tell you that there were dragons over those hills, and you couldn’t really do much to prove me wrong it would make sense for your whole notion of facts and accounts to be held from a different perspective. Teaching these investigative historical skills is equally as important as teaching content and Lee does a good job of creating hypothetical conversations between students that approximate what their reactions could be. Overall the reading reminded me of a video I saw awhile ago and I decided to include a link to that instead of a picture.

Blog post 1, Lemon

I have always believed that the fundamental problem with public education is that in order to give students an adequate one and prepare them for the “real world” students need to start well before they realize the value in it. This means that as educators we should not be surprised to be met with the “Idunno”. I have no doubt that inquiry-based learning is an effective method for students who make it through all the steps, but how do we get them there? And what happens to students who don’t put in the honest effort. In class sizes as large as is common in many districts it can be very easy for students to fake enthusiasm and slide under the radar. What can we do as educators to improve motivation? While there is no silver bullet, I think the most important things to consider when trying to motivate students to use inquiry style methods are relationships and real-world application.

Fostering healthy relationships with students can be difficult for many reasons. One of the most obvious is the difference in authority between teachers and students. Because an educator’s job is to get students to do work they generally don’t want to do, it can seem to students like their relationship with their teacher is antagonistic. The other big complaint (or at least one of the other big complaints) is usually “why does this matter to me” or “this doesn’t matter to me”. Most students (and many adults) lack the sociological imagination to see the ways that behaviors, events, individuals and organizations affect each other and all of us.

So in order to make effective use of Wolpert-Gawron’s inquiry method we need to make a conceded effort to form and maintain relationships with students. This may take time out of content and should be started at the beginning of the semester and maintained throughout. We also need to constantly be making real world connections to content. Students need to see that there is a real-world outcome to what they are learning. These things are much easier said than done and they require constant attention to student responses to lectures and discussions.

This is an example post, originally published as part of Blogging University. Enroll in one of our ten programs, and start your blog right.

You’re going to publish a post today. Don’t worry about how your blog looks. Don’t worry if you haven’t given it a name yet, or you’re feeling overwhelmed. Just click the “New Post” button, and tell us why you’re here.

Why do this?

The post can be short or long, a personal intro to your life or a bloggy mission statement, a manifesto for the future or a simple outline of your the types of things you hope to publish.

To help you get started, here are a few questions:

You’re not locked into any of this; one of the wonderful things about blogs is how they constantly evolve as we learn, grow, and interact with one another — but it’s good to know where and why you started, and articulating your goals may just give you a few other post ideas.

Can’t think how to get started? Just write the first thing that pops into your head. Anne Lamott, author of a book on writing we love, says that you need to give yourself permission to write a “crappy first draft”. Anne makes a great point — just start writing, and worry about editing it later.

When you’re ready to publish, give your post three to five tags that describe your blog’s focus — writing, photography, fiction, parenting, food, cars, movies, sports, whatever. These tags will help others who care about your topics find you in the Reader. Make sure one of the tags is “zerotohero,” so other new bloggers can find you, too.